Reviewed by Stephen Carter

The Cokeville Miracle and Freetown are fascinating glimpses into how Mormons approach faith-promoting stories, and how those stories interact with the core message of the gospel.

The Cokeville Miracle

The Cokeville Miracle releases in United States theaters 5 June 2015.

If you havent heard about the Cokeville miracle: in 1986, David and Doris Young (played by Nathan Stevens and Kym Mellen, repectively) took the children of Cokeville Elementary hostage, gathering them all into a classroom where they had set up a homemade bomb. They demanded a $2 million ransom for each child. But after a few hours, the bomb accidentally went off, though no one was killed. Davis reportedly shot the badly injured Doris and then committed suicide in the school bathroom. Afterward, some children described people in white as being at the scene just before the explosion, directing them away from the blast area and protecting them.

I grew up hearing the collection of tales that turned into the Cokeville miracle story, and all the feelings I had about it during childhood came right back as I watched T.C. Christensens (17 Miracles, Ephriams Rescue) movie portraying it. It is a religiously satisfying narrative. The concrete way the angels are described (many being the childrens ancestors), the way they drop in through the ceiling (like light bulbs), the way they gather to direct the blast, connects many religious dots: God is not only watching over our children, but enlisting the help of ancestors who dramatically affirm a strong, loving connection with their descendants. The story makes the link between the mortal sphere and the divine feel almost tangible.

The fact that the high-production-value Cokeville Miracle is aimed at the family movie audience drives many of the choices this potentially frightening narrative makes.

For example, early on, the story establishes Davids meanness and mental instability, but also his buffoonery. A few friends find him in a hotel room feverishly pounding at the buttons of a calculator while Doris exclaims, Hes mathematically proven how he can die and come back to life! And many of David and Doriss early scenes are accompanied by a crazy/goofy score.

A great many of the school standoff scenes are marked by humor that downplays David and Doriss threat. For example, a boy sees Davids guns and asks him, Why didnt you bring an AK-47? To which David retorts in all earnestness, That would be illegal! Another little girl constantly picks apart Doriss sentences.

Apart from a moment where the principal returns just in time to stop David from threatening to shoot a boy, David spends the standoff glaring moodily into the distance as Doris tries to keep the kids occupied, telling them, This will make a great story to tell your children someday!

Mellens portrayal of Doris, who is always balancing precariously between her worship of David and a nagging fear that he might be nuts, is the most interesting performance in the movie.

Interestingly, the standoff ends at the two-thirds mark in the movie. The last third is dedicated to the story of Ron Hartley (Jasen Wade), a police officer who is struggling with his faith in God because of the awful things he has seen in the line of duty.

He interviews people close to the school incident, uncovering each miraculous part of the story, but hangs onto his doubts until the movies last few minutes when he overhears part of a sermon from an open church classroom door and listens to Primary children singing A Childs Prayer. Heavenly Father, are you really there? And do you hear and answer every childs prayer? The storys overwhelming answer to the songs question is yes. The officer smiles and sheds a tear, and his children rush from the Primary room to hug him.

However, a few seconds later, an epilogue acknowledges that not all desperate prayers for safety are answered. We dont know why, it admits. But we should recognize the hand of God when we see it.

I agree. But the hand of God has done many things. For example, we are explicitly shown the hand of God in a very different story. The Book of Mormon tells about Alma and Amuleck being forced to watch the burning of women and children. Amuleck begs Alma to call down the power of heaven to save these innocents, but Alma tells him that he cant, that he feels God is allowing the wicked to fully condemn themselves and that these screaming martyrs are being taken straight to the bosom of heaven.

I can only imagine how well The Cokeville Miracles target audience would receive a movie about two prophets who watch as a school full of children burns down (which is what would have happened had the bomb gone off properly). But the Book of Mormons horrifying story can also be considered miraculous evidence of the hand of God.

This makes me think that miracle stories are often a diversion. Yes, they can be emotionally satisfying; yes, they can give us a sense of safety, justice, and divine love; yes, they can motivate us to engage in healthy behavior. But miracle stories almost always involve the physical world: they involve the saving of those things which are precious to us but which will naturally pass away (our crops, our children, our own lives). But the gospel of Jesus Christ is explicitly not about miraclesunless you are talking about the miracle of atonement and spiritual transformation.

And this is one place where the movie seems to entirely miss the boat.

The officers doubts about the influence of God in such an ugly world prevent him from praying with his family and going to church, disappointing his wife and children. As far as the film shows, Hartleys lack of faith is his single defining feature in their eyes. Not once does his family interact with anything about him but their wish that he would go back to being his old self and adhere to their spiritual practices. Not once is there a scene where his wife simply sits down to listen to him without judgment. He is a problem that needs to be fixed.

As Hartley uncovers the stories around the explosion, his wife keeps asking why he cant see whats so obviously in front of him. Toward the end of the movie, she delivers an ultimatum: Youre the best man I know, she says. But if you refuse to see reality, youre going to lose us. His value to her is based not on his core goodness, but on his willingness to believe what she does.

Most stories of spiritual progress start in the borderlands. Mary becomes pregnant out of wedlock, thrusting her outside the pale of Judaism. Job loses his riches, his family, his reputation, and his health. He refuses to accept the religious answers his friends give him for his misfortunes. Joseph Smith fears that the truth cannot be found on earth, which keeps him from joining the church his family prefers. These spiritual giants started their journeys in frightening places that their communities didnt approve of. But that is precisely the reason they made such great strides. Questions engender humility and fuel exploration.

And then there are normal people like you and me with our less-than-world-shaking lives, inevitably finding ourselves struggling with questions that threaten our worldview. We dont ask for these questions, they find us themselves. We are as frightened about their implications as our loved ones are about us. We suddenly find ourselves outside the community, lonely and scared. The thing we need most is for someone to stay with us as we encounter these questions. Someone who values usnot our beliefs. This is what Jesus did. He sat with the prostitutes, the publicans, and other outcasts. He was rarely seen with the religiously respectable or the politically powerful.

Jesuss question to us is not Do you have family prayer? or Do you go to church? or Do you believe in miracles? His question is simply, Who are you? A question whose answer is always changing, always invisible to the rest of the world, always a matter exclusively between us and God.

However, at the end of The Cokeville Miracle, the police officer gets spiritually fixed. He returns to the community and adheres to its beliefs and practices. The family comes back together, but misses an important opportunity to understand each other better.

Freetown

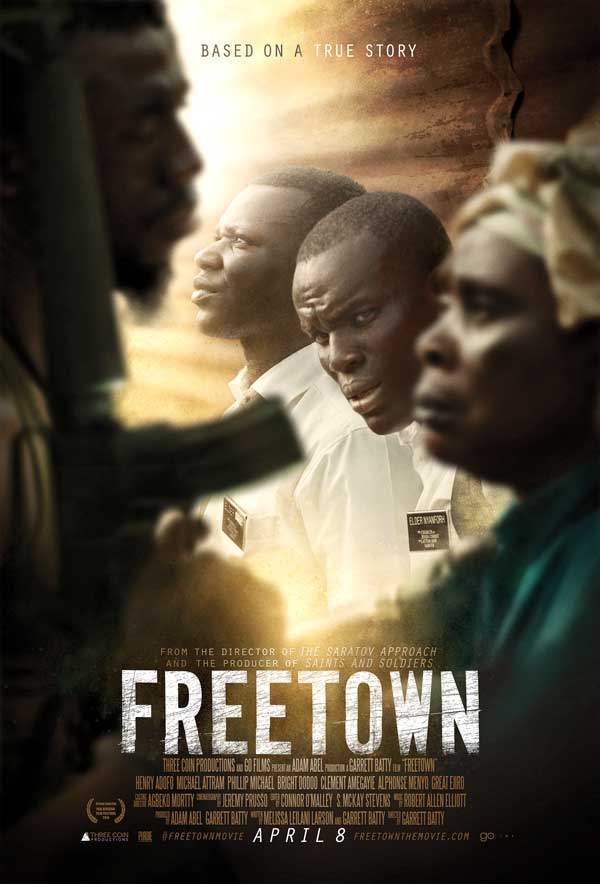

Freetown releases in United States theaters 8 April 2015.

If The Cokeville Miracle patrols the borders of what it means to be a believer, Freetown explodes them.

In some ways, Freetown (directed by Garrett Batty of The Saratov Approach) is a conventional faith-promoting, based-on-true-events story: a group of missionaries miraculously escapes war-torn Liberia into Sierre Leon. But the movie also breaks just about every rule in the faith-promoting-genre handbook.

First, this is a heavy, frightening film. It takes place in a political environment that seems to have no good guys. Members of the Krahn tribe have illegally retained control of the Liberian government after a lost election, motivating a group of rebels to strike back by sabotaging Liberias infrastructure and killing any Krahn tribespeople they find.

The film depicts the violence perpetrated during this time with startling directness. Some rebels leap from a truck in front of a man riding on a scooter, beating and then shooting him (off screen). Later, a missionary accompanies a husband who leaves his wife and daughter with some other refugees in a church house in order to find some food. The husband is shot on his way back as the missionary watches. The missionary trudges into the church house carrying a sack of food but unaccompanied; the wife looks up and begins to weep as her unsuspecting daughter sleeps in her lap.

But the most frightening scene is when two missionaries are captured with a few other people and shoved against a wall. The rebels go down the line, identifying some of their victims as Krahn. And then, as the camera abruptly shifts to obscure our view, the rebels shoot them.

Two freshly dead bodies on the ground, the rebels accost a Krahn missionary, but a nearby LDS Church member who is working with the rebels intervenes. I know these guys, he says. Theyre in my church. Ill take them to the labor camp. But this one is Krahn, says the leader. And he will be treated as such, the Church member replies as he drags them away.

At this point, we must stop to thoroughly understand what has just happened. In The Cokeville Miracle, the faith of a man who has a hard time praying and going to church is under suspicion, but in Freetown, a man who only a few seconds ago was complicit in the cold-blooded killing of two people, and doubtless in the killing of others on an almost daily basis, unabashedly describes himself as a member of the Church. And nobody questions his claimnot even the missionaries.

Can a man involved with genocide be a believer? Freetown seems to take the radical approach of defining a believer as any deeply imperfect soul: perhaps blind and destructive, but still on an unpredictable, eternal, and entirely personal journey of his or her own.

This widened view of belief also makes room for the movies main character, Phillip Abubakar (Henry Adofo), who is dispatched by the mission president at the beginning of the movie to keep the missionaries safe. Phillip is dedicated to the missionaries well being, but he is also a doubter. Indeed, he has adhered a Mark 9:24 decal to his rear window (help thou mine unbelief). He never relies on the unseen; rather, he works; he looks ahead; he bears the weight of the missionaries lives on his own shoulders.

Their journey (thirty hours of driving) is remarkable, the group evading danger many timesnot to mention Phillips Toyota Corolla managing to carry eight grown men through hundreds of miles of bad roads and dirt trails without breaking down or even getting a flat tire. And all this time, Phillip is at the wheel, navigating the checkpoints, finding food, and organizing the missionaries.

The missionaries and Phillip complement each other well. When the car finally runs out of gas in the middle of nowhere, they keep Phillips spirits up until they find a gas station. Then, when they arrive at the bridge into Sierre Leonclosed to them as each of the missionaries has forgotten his passportthe missionaries give Phillip the heart he needs to continue his journey. Phillip has plenty of room in his pragmatic world for the sometimes naïve faith of the missionaries, and there is plenty of room in their faithful perspective for his hard-headedness.

This same kind of space is offered to the Mormon rebel, who goes on a soul journey of his own, not toward adherence to Mormon customs, but toward a difficult, possibly fatal choice.

So, though there are some physical miracles along the way, the story focuses on the miracles taking place inside peoples hearts. One particularly moving scene involves Phillip talking with a missionary about when they found out about the priesthood ban. Being African men, the discovery was especially painful. But the missionary doesnt try to explain the issue away; he simply points out that were all changing, that were all trying to make ourselves better, and that our constant search for betterment is the crux of the gospel.

Later, the Krahn missionary says something to the effect of, Many horrible things have happened that will affect us permanently. We cant do anything about them. All we can do is try to make something good happen now.

Freetowns willingness to allow opposition to be potent and permanent gives these moments of grace an enduring power.

Link Download :

Free Download The Cokeville Miracle (2015) Full Movie HD

Stephen Carter, Sunstone Magazine. (A review of both Freetown and The Cokeville Miracle.) If The Cokeville Miracle patrols the borders of what it means to be a

Sunstone Magazine | Stephen Carter

Movie Reviews: The Cokeville Miracle By Stephen Carter Im certainly not the youngest person to helm Sunstone Magazine, Sunstone is a magazine

Freetown: Movie Reviews | Dawning of a Brighter Day

Freetown: Movie Reviews. April 8, 2015 8:53 pm \ 2 Comments \ by Andrew Hall. Reviews for Freetown, Moores reviews are syndicated to many newspapers.]

The Cokeville Miracle

premier bank secured credit card reviews southwest credit card application Magazine Site Last Movies The Cokeville Miracle.

Matters I MORMON PAGEANTS - Sunstone Magazine

the face over his SUNSTONE columns about homosexuals, Salman Despite this somewhat mixed review of his overall watch that movie with that little Jesus

AML Awards - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The AML Awards are given annually by the Association for Mormon Letters to the Brady Udall for The Miracle Life of Edgar Mint; Review. Jeffrey Sunstone 171

Meridian Magazine | LDS, Mormon and Latter-day Saint News ...

LDS News; National; Culture; World; Business; Reviews; Serializations; Meridian Magazine ran an article by JeaNette Smith entitled Can You Help Your

New Mormon Studies: A Resource Library 2009 Edition ...

Sunstone magazine through 1994, Salt Lake City: Sunstone Foundation, 1975-94. Sunstone Review. Volume 1:1 to 4:2 (29 Issues). IMDb Movies, TV

All comments on Anti-Mormon Training Center - YouTube

Share your videos with friends, family, and the world

Amazon.co.uk: Holly Edmunds

Sunstone 166 (Sunstone Magazine) 4 Apr 2012. Goodreads Book reviews & recommendations: IMDb Movies, TV & Celebrities :